On the Incarnation: Wild Indigo Guild #8 “Your Own Hands”

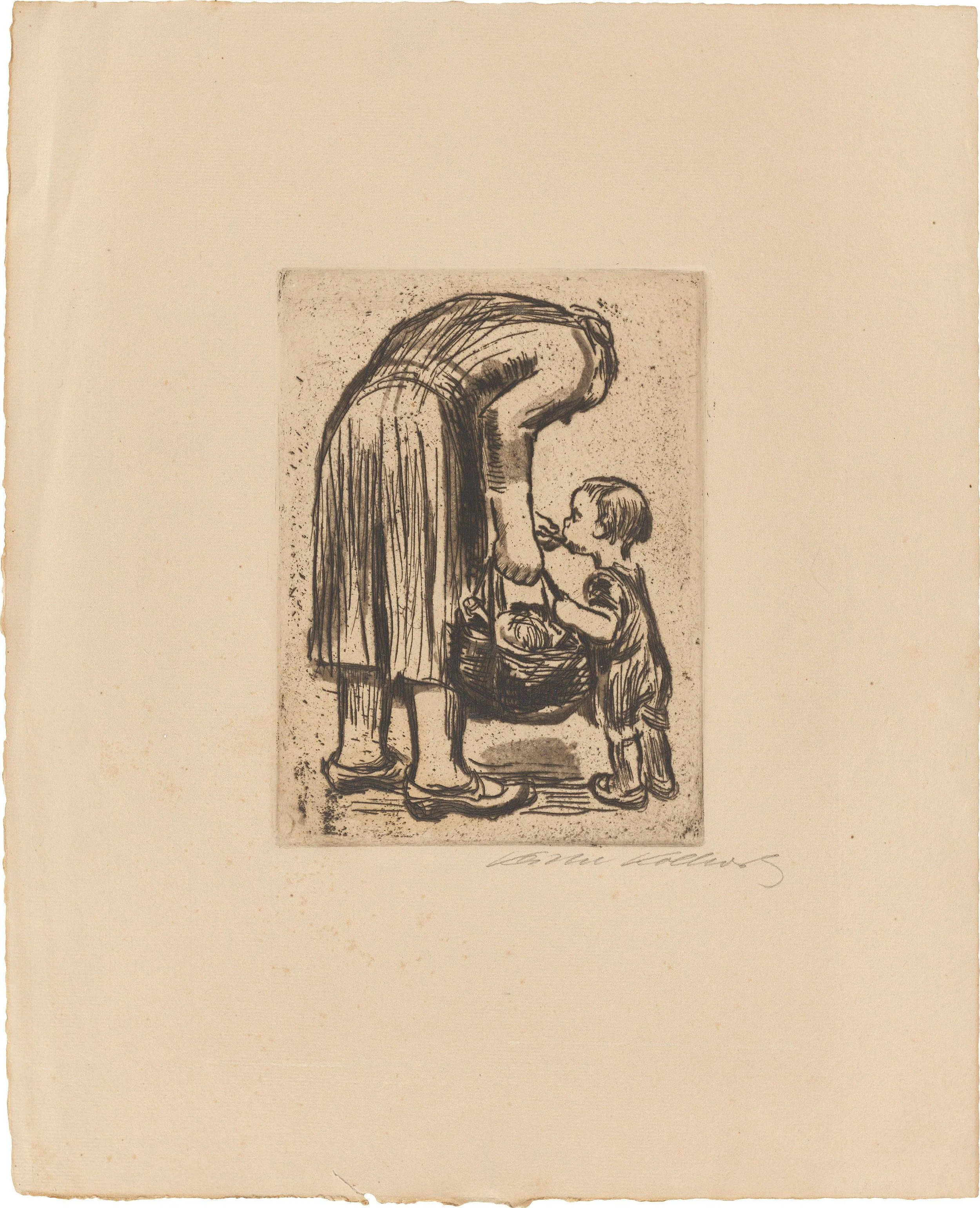

Standing woman feeding her child, Etching. Käthe Kollwitz, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

How does God keep in touch with you through your own hands?

What are you often doing when you sense the approach of a sense of inner quiet, a making-peace within, and a path to do so without, the rise of gratitude, generosity, good energy, confidence, grounded hope, of compassion for self and others?

Some activities can wrap us up tighter than a fiddle string with anxiety, weary us with care and worry, drive us with ego and ambition, or set in a mood to spark with irritation and irascibility. Some activities and involvements indeed become idols, energy and attention draining stand-ins that draw us away from God and our everyday opportunities to show-up in compassion, faithfulness, humility, creativity, commitment, care, friendship, generosity, and mutual-help.

But not all. In the midst of some creative works and useful activities of daily living, we find peace, contentment and gentleness in attending to what is at hand. Some works and activities engage our senses, mind, and hearts through the work of our own hands, preparing us to receive a moment of contemplative quiet, new perspective on a difficult situation, or a child unexpectedly bidding for our love and attention.

And if you can put down the knitting, whittling or bill-paying, and turn to the one who approaches you with kindness, openness of heart, listening and joy, then you have known the presence and working of true prayer.

And we need to see and lift up those things in our lives, whether they are creative pursuits, activities of daily living, or vocational tasks done well, as key places where God draws near, and we ‘practice the presence of God.’

In the Wild Indigo Guild formation pathway, we move through 8 themes, or gateways to experience and learning, arriving at the eighth and final theme-Working with your own hands. (1 Thess 4:11)

We might expand the quote a bit more, and say working with your own hands as a participant in God’s work of holistic restoration and new creation here and now.

We want to help one another (re)gain a sense of confidence in our ability to act in a restorative and healing way for the earth.

Many of us absorb enough voices that prophesy doom, such that what we humans then imagine that we can do little or nothing in the face of such global issues as climate change or biodiversity collapse. Or we get used to the thought on offer that humans are the problem, so it would be better if ‘we’ didn’t exist. And so anxiety and despair oppress us, fueled by what some modern therapies, and the desert fathers and mothers, would call “bad thoughts.”

Or we are handed a narrowed band of effective actions, such as individual consumer choices, or performative activism. We need better choices for consumption and political action. But when narrowed, these don’t hold out much for people who don’t already practice skills and codes for civic engagement with confidence, or possess the wealth to go out and buy a new electric car. Such frames for perception and options for action can deplete our own senses of “power, the ability to act,” leaving us less organized internally and externally for right action and generative work, less in touch with the truth of ourselves and of God.

Instead, the work of our own hands, undertaken in community and guided by inner truth, can be fruitful and life-changing today for you and the earth. And we can trust that as we begin again with what your hands know how to do, and with the peace of God which passes all understanding, a long-term, indeed eternal horizon, guides our steps. And humans made of earth, breathed with spirit, belong with God and the whole creation.

Hand from Chauvet Cave, copy, Claude Valette, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

And so, we ask for God to illumine those activities within your reach, to which your hands return, which call you forward with a sense of wonder, love, commitment and delight. Those works of your own hands promise a taste of peace and inner quiet, which allow your heart, mind and whole being begin to find a way forward, even, maybe especially in difficult situations. Such work of your own hands can bring true prayer, and a grounded sense of connection with body, earth, the holy One. Being so grounded, we may also receive a spirit of discernment and right action.

And such prayer may also be the work and prayer God has given you in order to participate in the divine work of salvation, the healing and restoration of humankind and all creation. What starts as picking up trash in a vacant lot may grow into a dependable habit of showing up for neighbors, and daily noticing what life grows up from the old foundations and street edges and wild corners of the life you share.

At this season of Christmas, (12 days!) we celebrate God drawing near to humankind and all creation in the birth of Jesus Christ. The incarnation means that God came to be with us in such a fashion that Jesus’s revelation of divine-humanity required the care, involvement, skill, thought, joy, mutual aid, boundaries, excess, good judgment, hurry, patience... and love of many other persons.

Where would the infant Jesus, the living word, creative wisdom, have wound up, without Mary and her treasuring heart, which knew wonder and grief, perseverance and poetic acclamation of justice and and God’s ability to act, without Elizabeth, who knew and loved Mary, surrounded her in loving connections and community, and joined her in hope and peace in her waiting, without Joseph’s commitment, roots, readiness for the road, building skill and design prudence, and openness to dreams? Jesus the child depended on the caring, guiding hands of other humans, and their hearts formed in tandem with their hands.

The Holy Family, Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, drawing, 1750s, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

So, we celebrate who God is and how God is with us and all creation very fittingly in simple little ways, like cutting out sweet cookies in the forms of hearts, stars, animals, and angels. As we savor their sweet goodness, those symbols also draw our hearts upward, in a movement beyond words, to the one who has joined with all manner of matter, and restored the whole creation to a pathway with God.

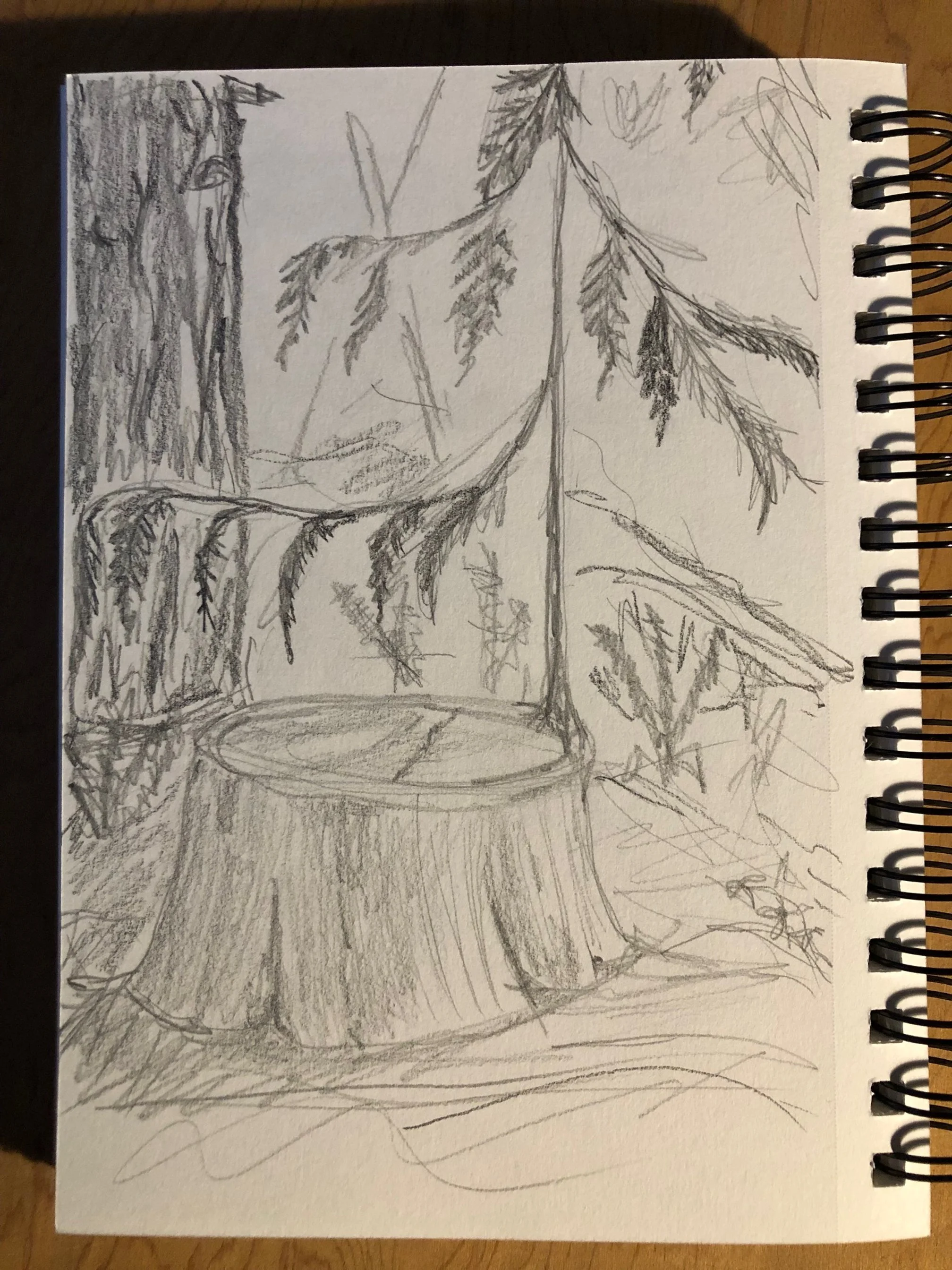

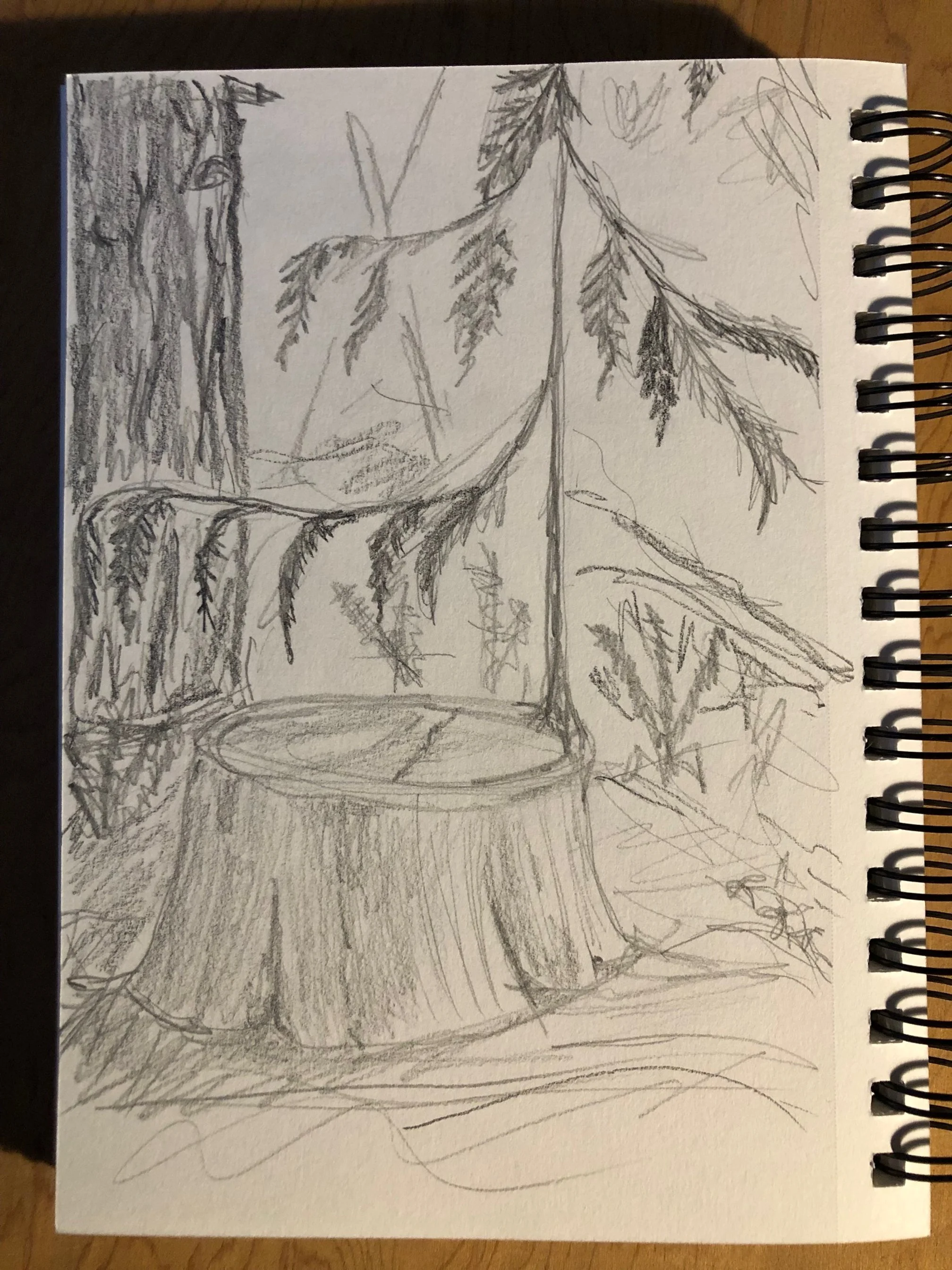

And we even hear of the coming of God in crisp words and image that could have been spoken by a tree-planter or gardener, who has spent hours of close attention to plants while their hands dug, pruned, and planted.

A shoot shall come out from the stump of Jesse,

and a branch shall grow out of his roots.

The spirit of the Lord shall rest on him,

the spirit of wisdom and understanding,

the spirit of counsel and might,

the spirit of knowledge and the fear of the Lord.

Along with the prophet Isaiah’s wonder-ful glimpse of God, we have heard many such glimpses of the divine one present and at work in the wider creation. And we have heard stories of how that wonder often re-appears as glimpses and as an ongoing companion in the works of our own hands. People tell of those works of their own hands that help them draw near to God, to ‘taste and see that the lord is good.’ What they have shared might help you look to the coming year with a sense of faithful simplicity, seeing more of God at work in you and around you everyday.

Gardening, composting, planting trees, walking, playing music, fishing, hunting, paddling, watching birds, drawing, cooking, weeding, quilting, picking wild berries from the forest edges and vacant corners, folding them in dough in the way your grandmothers hands did, sharing the good from the land with children and elders…

There are many ways that God draws near in the work of our hands.

What about you?

How does God keep in touch with you thru your hands?

How is God calling you to participate in the simple little way of restoring creation?

Acorn Abundance!

Last year I (John) was at my last fall retreat with families from The Open Door Church. I’d worked with the church for over 20 years, basically my entire adult life. Most years we would escape regular life for one weekend at a local retreat center. The fall retreat was bitter sweet last year. I had just announced I’d be finishing up my job as one of the pastors in just a few months. Evan and I had already started Wild Indigo Guild and I knew God was pulling, tugging, coaxing me to pursue this new work. I knew Evan had felt the same. I was excited but feeling vulnerable about this next steps God had before Wild Indigo Guild and my life.

I remember collecting acorns on that retreat with a few of the kids. There were some nice white oaks, Quercus alba, outside my cabin, one of my favorite trees in our region. The kids helped me gather more acorns than I needed, plenty. And we all had fun doing it. Kids love foraging. Those acorns, at least some of them, are now tiny trees in pots in my back yard, soon to be planted into larger pots when we start the Wild Indigo Guild nursery in the spring.

A beautiful and very old Pedunculate oak that Alyssa and I visited last May.

This year the church went on retreat without me, but with their new pastor, my friend, Rev. Jen Freyer-Griggs. When asked what they wanted to do on this retreat some of the kids said gather acorns! And… well… they did. In fact, they made acorn gathering into a full-on thematic event! That meant that I received a wonderful gift of over 10,000 acorns! It should be noted that two or three kids did most of that gathering! I’d love to say we were going to grow them all out and plant 10,000 white and red oaks this year, but we’re not there yet. So, what to do with all those acorns?

A handful of our 10,000 acorns.

Three easy things you can do with lots of acorns: my favorite… plant some trees, my second favorite, eat them! And the third option, feed them to your goats. If you don’t have goats, pigs like them too. Oh, and if you don’t have pigs, the deer and squirrels in your neighborhood will love them. I’m sure you can think of some other options too.

Native people throughout North America and throughout the world have used acorns for food for millennia. Oaks grow in arid climates, in wetlands, on Rocky Mountain sides, and in the Great Plains of the midwest. They grow from the east coast to the west and have fed people and creatures on this continent since time immemorial. Even Sam Gribbley of my favorite children’s book, My Side of the Mountain, made acorn pancakes. Not only are they great for people and mammals, oak trees support more insects than any other tree, which means they also support the birds the eat those insects. Want to support native ecosystems, plant more oak trees!

Last Saturday our Center Guild gathered for prayer, a wonderful and hearty meal, and to process acorns into acorn flour. We had a great time learning the process and having fun around the table. My plan is to make pancakes, like Sam, for our Center Guild meal in February, as long as we can get enough acorn flour ready for fifty or so pancakes. Our gathering this month was beautiful. As with our first two gatherings, we had almost as many children as we had adults. We gathered at Seedbed Farm in Monroeville, PA. Mark and Courtney Williams own the oldest house in the area, an 18th century log home, and they made it available for us on that cold Saturday morning. Photos don’t do justice to how cozy, warm and inviting their home really is. Before our meal we gathered around the wood stove for a time of prayer, singing of some Advent carols and reflection on the life of Saint Nicholas of Myra in the 3rd century AD.

Children and adults listening to Evan tell a story about St. Nick

There were seven year olds and 75 year olds gathered together and participating in prayer and story telling. I’m not sure what folks thought of eating acorns when I shared about the after dinner activity for this month. Acorns represent natures abundance but they aren’t something we eat in our 21st century world. The reality is that our forests provide millions… billions… of extra calories for wildlife and potentially for humans. Acorns represent God’s abundance to me. Some years, called a mast year, oak trees communicate with one another that its a good year to produce huge crops of acorns. These years the trees provide a feast for wild turkeys, deer, squirrels, black bear and many other forest creatures. Once I saw a black bear high up in an oak tree munching and crunching away. In centuries past our forests were also full of chestnuts, not today, but maybe again in the future we’ll harvest acorns and chestnuts each autumn.

Working together to get our crop of acorns ready to be made into flour was a great, all ages, all abilities, activity. The work of our hands to create healthy food for one another is what we’re all about. The work of our hands was a celebration of God’s abundance in our lives as we close out 2025, as we look forward to the birth of Jesus, as we remember the generosity of Saint Nicholas of Myra.

Acorns after the rough grind but before soaking.

Later Evan and my two sons continued this process in our dining room, removing the shells and grinding the acorns. And we still have so many acorns to go! Some for the goats and some will be planted.

It’s not hard but it takes time to process acorns and soak the tannins out of the nuts. The soaking happens after the process we did together last Saturday. It takes several days and many changes of water before the four is ready for its second grind. Tannins are very bitter and actually work as an anti-nutrient in the human body, absorbing nutrients from the body. Tannins have to be removed before we can eat them, not so for all those other creatures. But, after leaching out the tannins acorns provide healthy unsaturated fats, protein, calories and lots of nutrients. It’s one thing to harvest wild greens or mushrooms from the forest, acorns and other nuts can provide the foundation of calories we need.

Acorns ready for soaking to remove the tannins.

Here’s our process we used to make flour.

Crack the acorn shells. I like to us a mortar and pestle. We also tried out hammers and pliers, but the mortar and pestle was by far my favorite. The shells crack easily and the net can be removed pretty easily. Some nuts are discovered or even black. Throw those ones out. If there’s a worm, that’s ok, just toss that one into the woods too.

Course grinding of nuts. After the shells are removed we put the nuts into a hand cranked flour grinder. I bought my in a tiny village in rural Mexico. Its for grinding corn to make tortillas, but it’s great for this too. I adjusted the grind so the nuts are still a little chunky, but pretty small. I don’t want fine flour yet. We tried it and the found the finely ground nuts are harder to handle during the leaching process.

Leaching the tannins. We’ve tried two methods of cold leaching the acorns to remove the tannins. One option is to put the ground acorns in a muslin bag and soak them in a bucket of water. We change the water twice a day. This seems to work well, it’ll take about six days. The second method is to use a mason or fido jar. Just put the acorns inside with water. I then strain the water out twice a day using cheese cloth over the top of the jar. This is easy and seems to work even better and getting the tannins out.

Drying the ground nuts. We use a dehydrator to dry the nuts. We’ll also try out the mantle over the wood stove.

Fine grinding of the acorns. Finally, I put the acorns back in the mortar and ground them finely, making perfect flour!

Acorns after being shelled, roughly ground and soaked for six days to remove the tannins. Now ready to be dried in the dehydrator.

Our first attempt at pancakes was a huge success, meaning both of my teenage boys liked them. I simply mixed the acorn flour with a gluten free pancake flour. It worked really well at 1:1 ratio and at a 1:2 ratio as well as a 2:1! meaning the acorn flour is really versatile and tastes great.

Finely ground and ready for use!

A Reflection on MODULE 7: PARTICIPATE IN GOD’S RESTORATIVE COMMUNITIES

Module 7: Participate in God’s Restorative Communities

By John A Creasy

Module 7 of the Wild Indigo Guild program is one of my favorites to teach. “Participate in God’s Restorative Communities” is our theme. Our idea here is that restoration of creation and of humanity will happen in community and often from the edges, outside of where most people would expect to find power and leadership.

If I’ve learned anything over the past sixteen years with Garfield Community Farm its the importance of community and partnerships. Almost everything we do at the farm these days is in partnership with some other organization, community leader or person in the neighborhood. Our children’s education is in partnership with Brothers and Sisters Emerging, our food distribution is in partnership with Valley View Presbyterian Church, our permaculture teaching is in partnership with Three Sisters Permaculture, etc, etc. It’s not because we can’t do things on our own, but it is because we can do all these things better in community. Our partnerships make us stronger and make our community stronger too.

A beautiful example of forest, meadow and wetland edges.

In ecology we learn that “edge ecologies” are more dynamic and diverse than pure ecologies. We find nature existing with more diverse and dynamic partnerships in these edge spaces. For instance, the edge of a forest and a prairie will have species of both ecosystems interacting. And the edge will have some of it’s own species, plants and animals that only live where the two ecosystems merge. In session seven of our program we explore the permaculture principles: Expand the Edge and Value the Marginal. The conversation almost always goes from ecological systems of health and diversity at the edges to the human realities of marginalized people groups and ideologies being valued and lifted up.

I love edge ecologies, that’s where we find blackberries and raspberries, hazelnuts and wildflowers. That’s where the monarch butterflies find milkweed to eat and lay their eggs on. I also love hiking up mountains to the edge of the tree line, where trees grow small but survive for centuries feeding Clarks nutcrackers boreal chickadees.

It’s not a big leap to go from learning about the diversity and abundant potential of edge ecologies in our gardens and farms to the ethical imperative of diversity and value of the marginalized in our faith traditions. Throughout the prophetic books of the Bible the voice of God is proclaimed from the margins of the Israelite culture. It is not from the center that change ever comes, but from the prophetic margins, where courageous men and women proclaim new messages of hope and truth. The prophets spoke out against idolatry and injustice against the poor over and over again, calling for change and repentance.

WIG volunteers planting a hedgerow, a perfect example of an edge ecology between the road and a farm field, or often between two fields.

Through Wild Indigo Guild we are hoping to develop leaders who can grow food by expanding the edges and valuing the marginal through faithful land stewardship. We’re also hoping to develop leaders who have the courage to speak prophetic truth from the margins of our faith, calling for a refocusing of the message we proclaim, a message that always lifts up the oppressed and welcomes the stranger on the margin. Not only will leaders proclaim a prophetic message, we’ll also get out of the way when those on the margins are ready to lead. We hope to amplify the voices on the margins who are calling for “earth-care, people-care and equity for all God’s creation.”

Module seven is all about participation in God’s work at the margins to bring about faithful work of restoration and healing. At the margins, whatever that looks like for you, you’ll always find ways to connect and partner with a diversity of people who have a diversity of thoughts and opinions, but who all work together for the restoration of God’s diverse communities.

Apple Harvest, The Mystic’s Table Manners, Doing Good

A Sermon Preached by The Rev. Evan Graham Clendenin,

9th Sunday After Pentecost, 8/10/25,

Episcopal Church of the Holy Spirit, Vashon Island WA

Lectionary Texts: Isaiah 1:1, 10-20 Psalm 50:1-8, 23-24 Hebrews 11:1-3, 8-16 Luke 12:32-40

If you really want to learn to do good table manners, you should go see Henry Suso. If you want to learn good, go visit that mystic and saint, sit at his table, and see how he gave thanks. If you want to learn to do good, and to make an offering of thanks to God, simply sit down with Sweet Henry.

You would see how he prepared his food, and gave thanks, and welcome others at table. You’d see how he cut and enjoyed apples. And that might be a welcome little detail, given the overflowing apple harvest we can see this summer and fall. The trees in my neighborhood are loaded, and I can see the trees here on Vashon are cascading with apples and other fruit. And I know quite a few of you are orchardists.

So, Henry Suso was a Dominican brother, a variety of monk. Other Dominicans you may have heard of include Albert the Great, and his students, Thomas Aquinas and Meister Eckhart. Suso was a student of Eckhart. They were an order devoted especially to preaching and teaching. Henry Suso preached and taught along the Rhine river. Also, fun fact, his name Suso, is a variant of the word that means ‘Sweet’ in German. Suess or Siess. Heinrich Siesi. Sweet Henry.

He loved God, and felt things deeply, and he sought intense experiences and expressions of his desire for God, as he understood God at that time. Earlier in his life, as a young adult, he took this passion to rather gruesome medieval extremes. Long hours praying in uncomfortable positions, starving himself, sleeping little. He even got this great idea to sew tacks into his undershirt, in order, so he thought, to learn to suffer with Christ. His biographer didn’t think this was very good.

Henry also came to realize his extreme devotional contrivances were not good. Some of his study and devotion had been good, helped him to learn and mature, gain discipline, and guide his loving energies more truly to God and neighbor as himself. But it was time to out-grow some of these, and some, God had never wanted.

And Henry began to realize God saying something like: reality, reality itself would offer him plenty of ways to join in Christ’s suffering. Rough treatment and danger on the road, false accusation and betrayal by friends, sickness, failed harvests. Government contrived famines and land seizures. Feudal pretenders seeking authoritarian breakthrough thru corruption, cruelty and perception manipulation. …You all know what I’m talking about!

You don’t need to contrive sufferings, the world will bring more than enough. It’s less about the external suffering, and more about your inner presence to bear more of the suffering you and others face. The question is whether you face these sufferings of others and yourself with an inner freedom that lets your be with love, and act out of love and courage, a persistent and focused desire to do good ‘for the long haul’, to offer the substance of your life, despite it all, in thanks to God. God changes us inside, in ‘the heart.’

And it’s in simple activities of daily living, like how we prepare and share food at table, that a heart transformed by God is demonstrated. Henry loved apples, but earlier in life he would deny himself apples because he thought his enjoyment of the fruit was a sinful desire. Around that time, the apple harvest failed in the region. And something shifted in him, in his regard toward his desire for apples, in how he could see that God met him in his desires and his own being and in others. He prayed to God saying, ‘God if you want me to enjoy apples, please provide enough for all the community to enjoy them too.’

And wouldn’t you know, not much later, a noble stranger came by to eat with the brothers, and left them a nice big silver coin, enough to buy a whole crop of apples for the brothers to enjoy. So Henry enjoyed apples as a gift of God. He would take an apple and slice it into four pieces. Three he would peel, to remind himself of the holy trinity, one he would leave unpeeled, in appreciation of the fact that children at the time ate their apples unpeeled, and we might become as little children. (I know the peel is the most healthy part, we could tell him that now.) And he greeted and welcomed God at every meal, offering the Holy Wisdom food and drink, attending to them in gentleness and welcome.

Sunday Morning Breakfast, Horace Pippin, 1943, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

There come moments when we what we had thought we needed to do to get near God falls apart and flakes away. A devotion, a study, an ideal, some practice, habit, or ritual, some belief taught or caught by life, upbringing, education, the pressures of life, or one’s own false self pursuits…you come to find these are not what God wants. Isaiah and the Psalmist speak to this…

“I am weary of your offerings”

“Do you think I actually like the blood of goats?”

In such moments you may discover that the God of your understanding, your inner picture of the holy one, is undergoing subtle, and not so subtle, changes. Such movements and changes in our faith transform us, make our worship and prayer more truly a sacrifice that is ‘reasonable, holy and living’, - a practice of everyday gratitude and simple, persistent doing good.

And God gives us a Holy Spirit assist, a silver coin when we need it. The master will come and serve them, us, at his table, says Luke today. And we receive again the chance to learn to do good, and to give thanks to God, in worship, and prayer, and in all of life as we live it a day at a time.

Stages of Compassion

I (John) preached a sermon this past Sunday at Plum Creek Presbyterian Church on Lament and Compassion. The church is located very near where the Wild Indigo Guild (Center Guild) will take place starting this fall. It’s a beautiful area near Boyce Park and farms still existing in the suburbs.

I was asked to post my notes/manuscript by one of the parishioners. Here it is.

The Judgment of the Nations - Matthew 25

31 “When the Son of Man comes in his glory and all the angels with him, then he will sit on the throne of his glory. 32 All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats, 33 and he will put the sheep at his right hand and the goats at the left. 34 Then the king will say to those at his right hand, ‘Come, you who are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world, 35 for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, 36 I was naked and you gave me clothing, I was sick and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me.’ 37 Then the righteous will answer him, ‘Lord, when was it that we saw you hungry and gave you food or thirsty and gave you something to drink? 38 And when was it that we saw you a stranger and welcomed you or naked and gave you clothing? 39 And when was it that we saw you sick or in prison and visited you?’ 40 And the king will answer them, ‘Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did it to me.’ 41 Then he will say to those at his left hand, ‘You who are accursed, depart from me into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels, 42 for I was hungry and you gave me no food, I was thirsty and you gave me nothing to drink, 43 I was a stranger and you did not welcome me, naked and you did not give me clothing, sick and in prison and you did not visit me.’ 44 Then they also will answer, ‘Lord, when was it that we saw you hungry or thirsty or a stranger or naked or sick or in prison and did not take care of you?’ 45 Then he will answer them, ‘Truly I tell you, just as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to me.’ 46 And these will go away into eternal punishment but the righteous into eternal life.”

I’m reading a book with a few folks right now called “The Tears of Things,” by Richard Rohr. I bet you’ve heard that name before, or you’ve read some of his books or listened to his podcasts. In chapter 7 Fr. Richard opens up the book of Lamentations, a prophetic book of the Hebrew Bible, not one that we read very often in church. We don’t like to lament, do we. Our lectionary skips right over Lamentations except for the one hopeful section in the middle of the book. There are many places in the scriptures where God’s people lament, mourn, feel the deep sadness of creation’s suffering.

Jesus’ words in our Matthew passage remind us just how important compassion is to salvation. There is a definite link between lamentation and compassion. Jesus makes compassion the thing that opens the gates of heaven! Jesus suggests that the compassion that we have on “The least of these” opens our eyes to the Christ present within each and every suffering person.

What is compassion? First of all, passion is the feeling of emotion. When we feel passionate about something or someone its an overflowing of emotion… it’s about feeling… passion is any emotion felt at its fullest. The prefix “com” is related to the words community or comfort… it implies “with-ness”. Compassion is feeling of emotion WITH another. Compassion is feeling the pain, sadness, love… the emotional extremes of another.

Three Stages toward compassion.

The first stage is where we find the people who think they haven’t seen Jesus hungry, naked and suffering. In this stage we have no compassion, or we bury our compassion so we don’t have to feel anything or do anything. This is the stage where we victim blame, we come up with reasons that someone deserves to be hungry, deserves to be suffering. In this stage we cannot see Christ in the suffering of humanity. We blame the people of Gaza for the actions of Hamas, allowing us to ignore the suffering of babies, children and innocent people. We blame the poor for not working hard enough. We blame the sick for not taking care of their health. These people that never see Jesus in the eyes of another person, in the eyes of all God’s people, are those on Jesus’ left hand side, those who do not know him, cannot recognize him. There are so many reason we get stuck in the state of denial.

But, compassion will rise up in each of us. Compassion is Christ’s love welling up in our hearts, unifying us with others and with Christ.

This is when the the second stage of compassion arrises from the compassion of Jesus within us.

The second stage is when we see suffering and we want to take action to help. Suffering is seen as a problem and we believe we can solve that problem, or at least put our two cents toward solving the problem. Don’t just stand there… Do something stage! Here we begin the move from complacency and/or ignorance toward understanding and compassion. Jesus says, I was hungry and you gave me something to eat. In this second stage we see the suffering of other sand we desire to alleviate that suffering. We see Jesus in the eyes of humanity.

But, in our beginning to see and feel the suffering of the world many of us quickly try to solve the problems of the world, or at least do what we think is our part to solve the problems of the world. Don’t get me wrong, we should all be working to alleviate suffering in the world! In this stage we feed the hungry, we cloth the naked. But, do we sit with the lonely and listen? Do we visit the imprisoned and fully understand their suffering? Often not. This stage of compassionate action in the world leads to what I believe is the highest stage of compassion.

The third stage might be represented by flipping the Don’t just stand there phrase upside down… Don’t just Do Something… Stand there! There are a lot of people, most I’d say, who prefer to do something that makes them feel like they fixed a problem, so that they don’t have to feel the suffering of the world. But, Jesus includes two actions that are really hard for those of us who like to “do” or “give” and then walk away. Jesus says, “I was sick and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me.’”

Have you ever cared for someone who was sick? Have you ever cared for someone who was dying? Some of us care for our parents when they near the end. But, even that is rare these days. While nursing homes can be a great tool in caring for the elderly, they can also become place of abandonment of our elders. I think many elderly people in nursing homes feel like they’re imprisoned.

My dad worked for a large church in the north hills of PIttsburgh. He tells a story of the lead pastor asking who was available to go to the local nursing home. None of the pastors or staff wanted to go, but they did make it a monthly practice. My dad decided he go and over time it became of the most meaningful parts of his ministry in the church. They would lead a short service with some songs, but mostly he would sit with people, hold their hands and listen to their stories. My dad, not an ordained pastor, became the pastor those in the home. He saw Jesus in their eyes, and likewise they saw Jesus in his.

I have to admit, I am a problem solver. I thrive in situations where I can identify a problem and find solutions. As some of you may know, I’m a permaculture designer. In permaculture we looks to create ecological landscapes that support biodiversity while also producing food and fiber. Permaculture is about getting all that we need from nature while at the same time seeing nature restored to health. Nature is suffering, just as human beings are suffering in our world today. I love permaculture because we use the principles and practices to identify problems in nature and solve them, flipping the problem into the solution is one of the attempts in permaculture. Let me give an example: One of the gardens at our farm is on a hillside. When we first started to try to grow vegetables on that plot of land we realized a big problem, when it rained hard water was eroding the good soil to the bottom of the hill. We dug swales to catch and store the water deep in the soil, slowing it down and sinking it in. The excess water became a solution to our water needs, no longer a problem. I love those sorts of problems! We come out the other side better off than where we started!

But, over the past few years I’ve learned many lessons about problems I cannot solve. I see suffering not only in humanity but in all of creation… suffering that is caused by human greed. Climate change and deforestation are causing massive changes to local ecological systems. And we know that climate change is causing immense human suffering, unthinkable tragedies. We remember the children who died in Texas while at summer camp. We remember the large scale destruction in the North Carolina last fall. We remember the mega-fires that wiped out 25% of ancient giant sequoias in 2022 and 2021.

Our compassion leads to solidarity… with-ness… no matter the outcome of our problem solving.

I’m continuing to try to solve problems, but our love of people and our love of creation leads us to compassion and solidarity that does not hinge on the effectiveness of our problem solving.

Our passage today is quite remarkable. These are Jesus’ words making it very clear how it is that we receive eternal life - and it has nothing to do with praying the “sinner’s prayer,” does it? Instead, according to Jesus in Matthew 25, compassion is what demonstrates our belonging in God’s eternity.

The suffering of humanity IS the suffering of Christ. The Christ is present in all of creation, The Christ is present with all of who suffer, The Christ becomes present to us through all of creation. When we begin the journey of lamentation, of allowing ourselves to know the pain and suffering of the world, we begin to see that Christ is present to us through that suffering. This is a hard teaching, I know. But this is the full circle that we enter into when we feel compassion which leads us to action. Our action in the world just might lead us to real connection to Christ through our connection to one another.